The videogame film adaptation has a sorry history. Street Fighter; Super Mario Bros.; almost the entire filmography of Uwe Boll. That the barely-passable Tomb Raider with Angeline Jolie is generally seen as the pinnacle of the game to film transition speaks volumes.

The problem is that videogames just aren’t films; compared to what cinema can offer, videogame narratives are usually clumsy, shlocky and basic. Only natural, then, that a film adaptation using said narrative won’t come out well. Even recently lauded examples of videogame narrative such as Mass Effect and Bioshock appear weak when compared to their screen equivalents. Mass Effect‘s story is derivative of any number of SF TV shows and books, and Bioshock is an interesting idea wrapped up in 10 hours of carnage. Ico and Shadow of the Colossus are often held up as examples in the ‘games are art’ argument but as films they’d be nearly unwatchable, unless they were part of the beardy ‘slow cinema’ movement.

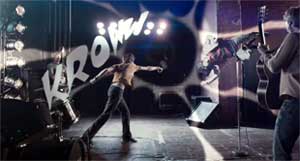

Scott Pilgrim versus The World is not a videogame film adaptation, but it is a videogame film. The source material — a series of graphic novels by Bryan Lee O’Malley — already presented a world in which videogame logic sat happily alongside ordinary, real-world logic, but in the film adaptation Edgar Wright ramps it up even further, bringing sound and animation into the mix while never letting the world feel incoherent. The videogame references aren’t just an extra layer bolted on top of the film; they pervade the film completely.

Scott Pilgrim versus The World is not a videogame film adaptation, but it is a videogame film. The source material — a series of graphic novels by Bryan Lee O’Malley — already presented a world in which videogame logic sat happily alongside ordinary, real-world logic, but in the film adaptation Edgar Wright ramps it up even further, bringing sound and animation into the mix while never letting the world feel incoherent. The videogame references aren’t just an extra layer bolted on top of the film; they pervade the film completely.

Edgar Wright has previous form in this area. His sit-com Spaced can be seen as a proving ground for placing videogame aesthetics and logical norms alongside nominally reality-grounded scenarios. First-person perspective is used, arguments turn into matches of Tekken, drunken nights out turn into Resident Evil rescue missions and bitter emotions are vented through the means of drowning Lara Croft.

Edgar Wright has previous form in this area. His sit-com Spaced can be seen as a proving ground for placing videogame aesthetics and logical norms alongside nominally reality-grounded scenarios. First-person perspective is used, arguments turn into matches of Tekken, drunken nights out turn into Resident Evil rescue missions and bitter emotions are vented through the means of drowning Lara Croft.

With the seamless way in which the Spaced narrative jumped between reality and fantasy without any fourth-wall breaking comment from the cast, the Scott Pilgrim series seems like a natural fit for Wright. Scott Pilgrim exists in a world in which vegans have superpowers, boyfriends can punch holes in the moon and you can take shortcuts through tunnels in subspace. Likewise in Spaced, gangs of youths can be taken out with imaginary weapons and Matrix-style agents are fought in the pub with Kung-Fu (alongside a pint and a packet of crisps).

Bitpunk

In Pilgrim, the era in which most of the videogame aesthetics are borrowed from are clearly from a generation earlier than that of the Pilgrim cast. Though the fight sequences hark back to ’90s arcade fighting games — chiefly from the Capcom stable — the visual effects tend toward the pixellated and chunky, from the Universal logo (with an accompanying chip tune rendition of the Universal theme) to the extra life icons and other HUD iconography visible through the film.

In Pilgrim, the era in which most of the videogame aesthetics are borrowed from are clearly from a generation earlier than that of the Pilgrim cast. Though the fight sequences hark back to ’90s arcade fighting games — chiefly from the Capcom stable — the visual effects tend toward the pixellated and chunky, from the Universal logo (with an accompanying chip tune rendition of the Universal theme) to the extra life icons and other HUD iconography visible through the film.

Music from both The Legend of Zelda and the Final Fantasy series plays regularly. While the soundtrack is mostly hipster indie rock, the Nigel Godrich score and the incidental effects are largely all 8-bit renditions, dating this particular aesthetic to the NES era — or in other words, before any of the Pilgrim cast would have been born.

This is a group of people that may be nostalgic for Final Fantasy VII, but not Final Fantasy II. This mixture of ’80s gaming aesthetics and present-day scenarios and characters places the film firmly into the nascent Bitpunk genre, typified by such indie fare as Spork, set in what is clearly the present but also in thrall to ’80s technology and culture. In Pilgrim, Young Neil may be seen regularly with a Nintendo DS Lite but he lists Zelda and Tetris as two of his favoured games. Pilgrim’s band is named after an element of Super Mario Bros. 2 and Pilgrim’s final fight is against a man who jumps like Donkey Kong.

This anachronistic style doesn’t make the film feel like it’s lacking in authenticity, though it will resonate clearer with people in their thirties rather than those in their twenties. It is instead a testament to Wright’s skill as a director and O’Malley’s strong source material that the film never feels gratuitous or cheap. Videogame logic may not be real world logic, but it is nonetheless a logic in its own right. So, Pilgrim’s use of an extra life and a replaying of the final minutes of the film having failed initially is very clearly videogame logic and perfectly acceptable in the context of either videogame or a bona fide videogame film.

This anachronistic style doesn’t make the film feel like it’s lacking in authenticity, though it will resonate clearer with people in their thirties rather than those in their twenties. It is instead a testament to Wright’s skill as a director and O’Malley’s strong source material that the film never feels gratuitous or cheap. Videogame logic may not be real world logic, but it is nonetheless a logic in its own right. So, Pilgrim’s use of an extra life and a replaying of the final minutes of the film having failed initially is very clearly videogame logic and perfectly acceptable in the context of either videogame or a bona fide videogame film.